Tehran’s streets, with their chaotic traffic and exhaust fumes, are a far cry from the tranquility of Laleh Park, just a stone’s throw away. On an autumn morning, we wandered through this green oasis, only to be struck by an odd sound: German. In Tehran. It wasn’t an isolated case. A small group of young people were scattered across the park, hunched over their books, preparing for a future that for many, can only exist abroad.

These students, like so many others, are participants in a growing exodus from Iran. They are leaving because their country no longer holds promise for their aspirations, no matter how hard they work, no matter how educated they are. One young man, studying German as part of his migration plans, told us: “There is no future here. Many of my friends who finished their studies here do not work in their field of expertise, and their salaries are extremely low”. Another student told us, “I studied industrial design. Now I sell scarves online.” Her voice cracked because she knows the game: side-hustles are now careers, not the stepping stones they were before.

Disappointment and frustration are also shared by Iranian students in foreign universities.

I graduated top of my class in electrical engineering, ” says Arman) pseudonym (, now a master’s student in Berlin. “In Iran, every position was already reserved for someone with connections. I applied for twenty jobs. I was never even called in for an interview. My family said: go, before the door to your future closes shut.”

“I love my country,” says Nazanin (pseudonym), who now studies architecture in Munich. “But love doesn’t pay the rent. My father’s pension is worthless, prices rise every day, and the government keeps sending money to groups abroad while hospitals at home can’t even provide basic treatment. You can’t dream when you’re just trying to survive.” “Medicine was my passion,” says Reza (pseudonym), who left Tehran University after passing the German language test, “But every senior doctor I knew was trying to leave too. The hospitals are politicized, you’re either loyal to the system or your career stagnates. I realized the only solution was emigration.”

According to the World Bank, Iran’s youth unemployment rate (ages 15–24) remains above 22%, while the rate for young women exceeds 34%. These are not just abstract indicators; they translate into millions of years of education that yield neither jobs nor dignity. With these figures, it is no surprise that Iran witnesses a surge of students fleeing to Europe and other destinations. UNESCO estimates that more than 110,000 Iranians are studying abroad, and research indicates many will not return, resulting in a permanent loss of highly educated talents.

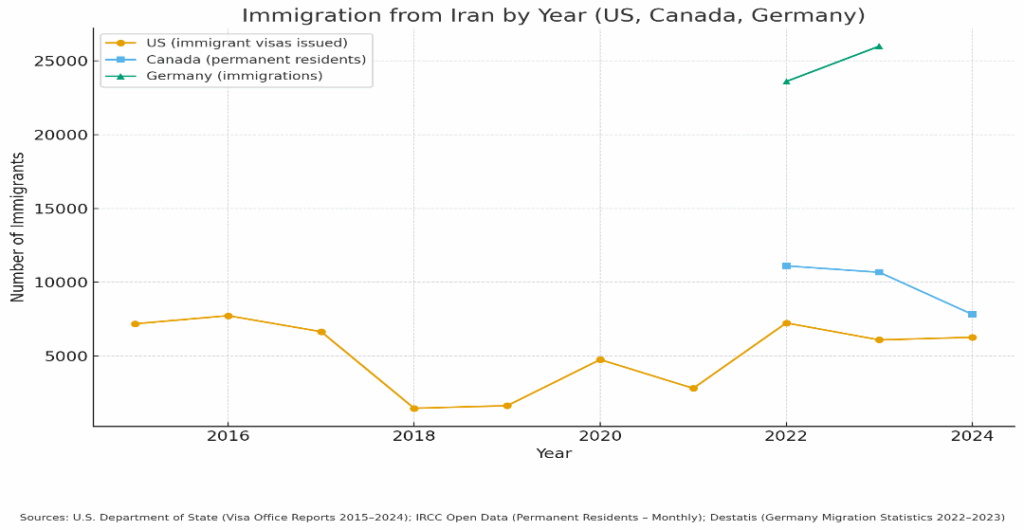

The outflow is significant: according to the “macrotrends” website, the net migration from Iran between 2021 and 2024 is approximately 1.2 million people, and as stated by the Farhikhtegan newspaper, the official mouthpiece of Tehran’s Islamic Azad University, approximately 6500 doctors and medical specialists left Iran in 2022.

Economists warn that losing human capital at this scale undermines innovation, productivity, and long-term growth. An economy without hope is an economy without investments, public or private. The ongoing sanctions, the activation of the snapback mechanism, and the regime’s insistence on implementing its military and religious plans are expected to increase the number of applications to study abroad and the number of people learning foreign languages. In Tehran, the streets may be crowded with people, but the ones who matter, the educated, the talented, the dreamers, are already making plans to leave.

Photo credit:

“Students (Shiraz, Iran)” by Sasha India, licensed under CC BY 2.0.