Dry dams, antiquated and wasteful agriculture, corruption and denial: this is what a nation looks like when it has walked with eyes wide open into an existential crisis

In the midst of another scorching summer, with temperatures exceeding 50 degrees Celsius in certain regions, Iranian citizens are awakening to a reality that unsettles even the standards of a nation inured to crises. On July 30, the website IRAN WIRE published the story of Amir, a Tehran resident grappling with lengthy water outages several times a week. Two water tanks were installed in Amir’s building in hopes of addressing the water cuts, but according to Amir, “The tanks don’t last more than one or two hours,” and families with toddlers still experience significant hardship during water outages.

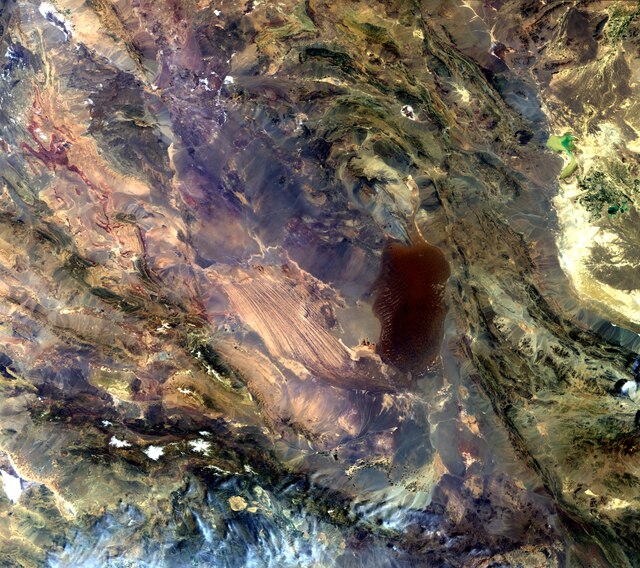

Water sources drained to exhaustion, reservoirs that have dried up, lakes transformed into deserts, and residents contending with daily water rationing—all these compound President Pezeshkian’s official warning published last July, stating that the country’s water reserves are expected to be depleted within mere weeks unless dramatic change occurs.

The depth of Iran’s general water crisis can be gauged from the situation in its capital, Tehran. The capital’s metropolitan area, home to approximately 20 million residents, faces an unprecedented collapse of its water supply system. The dams providing water to the city are in critical condition: water reserves in Tehran’s five main reservoirs have dropped to barely 13% of their capacity, with the critical Lar dam almost completely empty at just 1% of its capacity. The most striking example is the Amir Kabir dam on the Karaj River, a vital water source for area residents. In March 2025, a comparison between two photographs of the dam circulated on social media. One from August 2024 shows clear blue waters reaching the hills, another from the same location in February 2025 reveals a dry, cracked lake bed. The water had simply vanished.

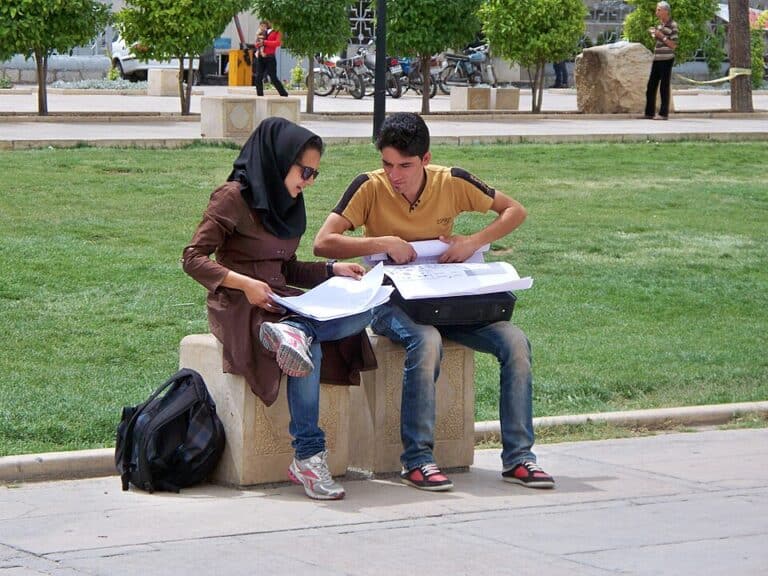

The critical situation has forced the government to take extraordinary measures. On July 23, Iranian authorities announced a mandatory furlough in Tehran and 24 additional cities to conserve water and electricity, while considering granting an entire weeklong furlough for residents to temporarily leave the capital. Government spokesperson Fateme Mohajerani announced the enforced hiatus on social media platform X and suggested citizens use the day “for rest, short travel, or spending time with family.” Despite the regime’s claims that there is still no water rationing for citizens, reality tells a different story. Authorities have reduced water pressure in Tehran by nearly half, and water is now being transported to the capital by tanker trucks, with residents who can afford it rushing to install private storage tanks.

The crisis in Tehran reflects a severe and alarming nationwide trend. According to official data published in early August by the regime-affiliated news agency Tasnim, 57% of Iran’s reservoirs are empty. According to the Iranian Ministry of Energy, certain provinces report levels of up to 98% depletion. More than 40 cities across the country are dealing with water rationing and prolonged outages, with some areas receiving water for only two out of every 48 hours—this in temperatures reaching 50 degrees Celsius and above. In a country of 88 million inhabitants, water insecurity has become the norm rather than the exception.

The Truth Flows Slowly, or Not at All

Despite the deepening of the crisis, Iran’s Islamic Republic insists on presenting the water system collapse as a cosmic matter beyond human control. According to official spokesmen, this is the “inevitable result of global climate change,” “divine punishment,” or even “part of the hydrological war being waged by regional powers against Iran.” Simultaneously, the regime conducts public campaigns calling on citizens to “show responsibility” and reduce household consumption—as if the nation’s future depends on the shower duration of every child in Tehran.

Yet this rhetoric grates against reality. Household consumption accounts for only approximately 6% to 9% of Iran’s overall water waste. Over 80% of Iran’s water consumption is absorbed by industry and traditional agricultural systems that rely on water-intensive crops such as rice, apples, and pistachios, often in arid areas lacking adequate infrastructure. The government’s attempts to blame the public reflect a transparent effort to deflect discussion from the real causes of the crisis: failed management, chronic corruption, and consistent disregard for professional recommendations over decades. Instead of leading deep systemic reform to address the roots of the problem, the regime continues to point an accusatory finger at citizens, provide meteorological excuses, and content itself with moral preaching. But the Iranian public, watching taps run dry and the soil crack, is no longer convinced by the regime’s explanations. The prevailing public sentiment is one of abandonment, of a state that refuses to take responsibility.

This sense of abandonment and neglect by the regime intensifies when contrasted with the water situation in comparable countries. On the other side of the Gulf, nations with similar, and even more severe, climatic conditions are actually thriving. The United Arab Emirates, a desert nation with less precipitation than Iran, invested in the early 2000s in establishing one of the world’s most advanced desalination systems. Today, over 90% of water for household and industrial use in the Emirates comes from plants that convert seawater to drinking water. Dubai, a city where life expectancy is growing and the economy flourishing, does so while relying almost entirely on natural water sources.

Saudi Arabia has also undergone profound conceptual change. Alongside investments in desert agriculture technologies and smart irrigation sensors, the Saudi government has promoted agreements with international companies to establish large desalination facilities and implemented strict regulation on water consumption in the agricultural sector. Even Jordan, one of the world’s poorest countries in per capita water resources, has developed national water programs in the past decade that include wastewater recycling for irrigation, regional projects for hydrological cooperation with Israel and Palestine, and support for household water conservation infrastructure.

In Iran, by contrast, desalination facilities are built slowly and with inflated budgets, sometimes with geopolitical considerations and Revolutionary Guard interests in mind. Water recycling is virtually nonexistent, infrastructure upgrades are stuck in countless bureaucratic obstacles, and public discourse is dominated by religious and political distractions.

Not a Matter of Weather, but of Deaf Ears

Iran’s water crisis is not a sudden event. Iran’s water crisis was predicted, studied, and foreseen by professionals who warned repeatedly over recent decades, but their warnings fell on deaf ears. According to Mehdi Fasihi Harandi, a researcher at the Presidential Center for Strategic Studies with a doctorate in water resource management and planning, “It didn’t take genius to predict Iran’s current water situation and its crisis, and we didn’t need to be Nostradamus; it was clear as day that this would happen.”

More than a decade ago, in 2013, then-Iranian President Hassan Rouhani declared that “Iran’s water shortage is an “historic” issue and can only be resolved through “national will,” — a call that echoed in the empty air of inaction. That same year, Agriculture Minister Issa Kalantari sounded even more desperate: “The water crisis is the main problem that threatens Iran… it is more dangerous than Israel, USA or political fighting among the Iranian elite. If the water issue is not addressed, Iran could become uninhabitable… In 30 years Iran will be a ghost town” Kalantari likely didn’t mean this literally, but today, in 2025, this prediction is closer than ever to realization.

Energy Minister Hamid Chitchian also warned at the time that the model based solely on dam construction had failed: “The water sector’s situation has reached “critical levels.” Past approaches focused on dam construction and increasing storage capacity are no longer appropriate solutions.” However, instead of promoting additional solutions to address the crisis, the regime continued investing in ostentatious infrastructure without environmental coordination.

In 2017, the words were spoken even more harshly by Issa Kalantari, then head of the Environmental Protection Organization: “Not even a foreign enemy ruling this country would have been able to destroy natural resources and the environment, as what has happened in the past years. We have experienced any kind of ecologic disaster within the past four decades. Before this, many of the country’s environmental indicators, such as water, we’re in a good position.” In 2021, parliamentarian Mohammad Reza Asafari from Markazi province also warned of the crisis’s severity and summed it up with disturbing simplicity: “The problem of water shortage in the country, especially in Markazi province, is serious. We will face a serious water crisis soon, and this will create many problems for agriculture and animal husbandry”

End of Angry Prophecies—Beginning of State Collapse?

Today, as public outcry grows and protests over water shortages become common even among residents not identified with the political opposition, it appears that zero hour—when there will be no water in the taps—is no longer a future scenario. It is here. Despite repeated warnings, the systemic, political, and managerial failure of Iran’s Islamic Republic regime has brought the country to the point of no return.

The path to recovery will require not only unprecedented investment in infrastructure but profound consciousness change in the systems of government. As long as the regime continues to treat citizens as the source of the problem and fails to invest genuine efforts in finding solutions and implementing them, the taps will continue to dry up—along with the nation’s hope.