The trial of Kulthum Akbari has gripped the nation: a woman accused of marrying, poisoning, and profiting from elderly men. Beyond the crimes, her case sheds light on culture, religion, and the silent suffering of the aged.

In the lush northern province of Mazandaran, where rice paddies stretch endlessly beneath misty skies, life tends to move at a gentle rhythm. Villages are quiet, neighbors know one another by name, and nothing ever seems truly hidden. That is why the story of Kulthum Akbari, a fifty-seven-year-old woman now on trial for a string of murders, has left the country in a state of disbelief. For nearly two decades, she lived among her neighbors as a seemingly ordinary woman. In reality, investigators allege, she was quietly weaving one of the darkest criminal legacies modern Iran has ever known.

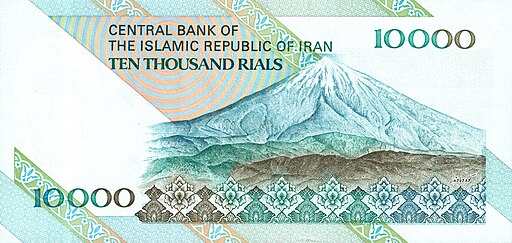

The accusations are chilling. According to prosecutors, Akbari targeted elderly men, widowed, lonely, often wealthy, and ensnared them through temporary marriages, a practice unique to Shi’a Islam known as sigheh. On the surface, sigheh was designed to provide companionship under religious sanction: a contract-bound union lasting days, months, or years, with a dowry agreed upon at the outset. For devout families, it was a way to maintain virtue within the bounds of law. For Akbari, investigators say, it became a weapon. She would demand lavish dowries worth millions of tomans in each marriage – sometimes in cash, sometimes in property – and once secure, begin a slow and deliberate poisoning.

The method was insidious. Traces of blood-pressure pills or diabetes medication, sometimes laced with industrial alcohol, slipped into tea or meals. The victims did not die immediately. They weakened, fell ill, and were sometimes rushed to hospital – accompanied by Akbari herself, who appeared, at least outwardly, as a devoted partner. But the steady drip of toxins would soon do its work, leaving doctors to sign off death certificates under the natural causes expected of men in their seventies or eighties. For nearly twenty years, no one connected the dots.

That silence broke in 2023, with the death of Gholamreza Babaei, her last husband. When the 82-year-old collapsed after drinking tea she had served, his relatives refused to accept the convenient explanation of “old age.” They demanded an autopsy. Toxicology reports told a different story. Police began re-examining older deaths linked to her name, uncovering a pattern that stretched back across two decades. At least eleven men, possibly more, had died in strikingly similar circumstances.

Her notoriety reached beyond the courtroom this spring when a character bearing the same name appeared in Paytakht 7 (Literally “Capital”), the latest season of Iran’s most beloved television comedy. In an April episode, the casual introduction of a “Kulthum Akbari” character instantly caught viewers’ attention. Within hours, the moment had gone viral. For some, it was an appalling lapse of judgment: how could a family sitcom invoke the name tied to Iran’s most notorious alleged serial killer? Others defended the choice as satire in its sharpest form, a way to laugh at fear and hold a mirror to society. The scene sparked a firestorm across Persian social media: hashtags multiplied, clips replayed millions of times, and commentators debated the blurry line between entertainment and exploitation. What began as a brief fictional cameo turned into a national conversation about crime, culture, and the uneasy ways a society processes collective trauma.

Now, as she sits in the courtroom of Sari, the provincial capital, the woman once seen as quiet and unassuming is at the center of a storm. Journalists describe her demeanor as unnervingly calm. She has admitted to parts of the accusations, though she insists she never set out to kill. “If I had known it would come to this, I would never have done it,” she told the judges. At another point, clutching a Quran, she swore: “If I am released, I will never repeat my actions again.”

For the families of her alleged victims, such words ring hollow. “We only want justice, and we do not want my father’s rights to be trampled,” one daughter told reporters during the trial. Her plea echoed the grief of many others who believe their loved ones were betrayed not just by Akbari, but by a system that failed to see the pattern until it was too late.

But justice, in this case, has a wider resonance. The Akbari trial has ignited a fierce debate in Iranian society, one that extends far beyond the crimes themselves. It has forced the nation to confront the uneasy place of sigheh within modern life. Supporters of the practice argue that it offers legitimacy and protection, especially for widows, divorcees, and men living alone. Critics counter that it reduces women to contracts and creates opportunities for exploitation. In Akbari’s case, the roles seemed inverted: a woman, rather than being exploited, allegedly used the institution itself as a trap to exploit men at their most vulnerable.

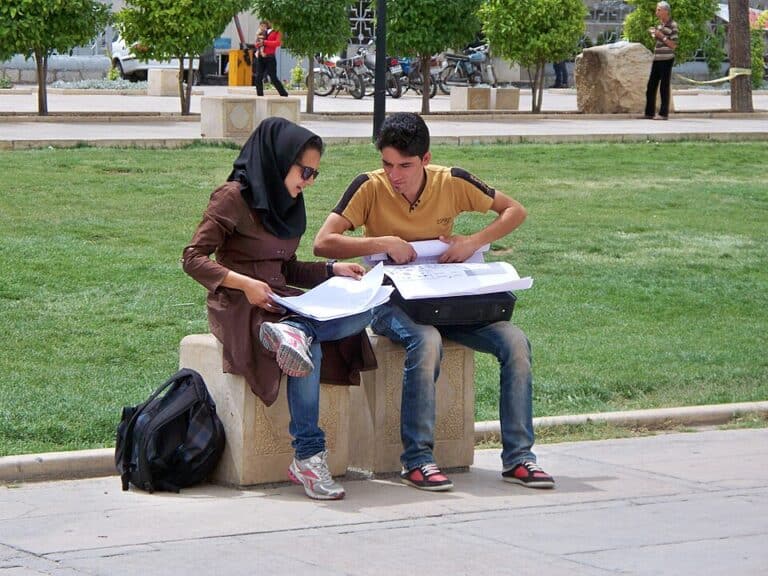

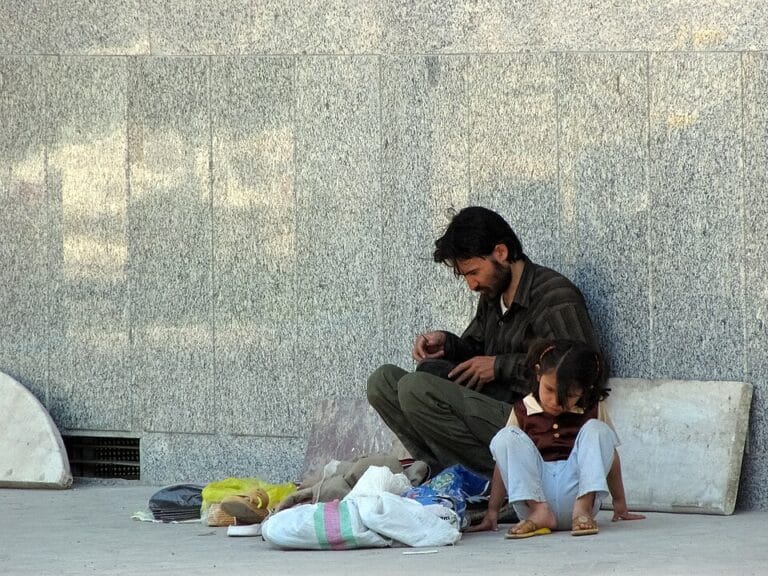

The debate is not only about gender. It is also about age. Iranian society, like much of the world, is grappling with an aging population. Elderly men, especially those left without partners, often live in quiet isolation. They become easy targets, not only for financial fraud but, in this grim instance, for predation dressed as intimacy. To many commentators, Akbari’s alleged crimes are less a personal aberration than a reflection of systemic neglect: a society that does not yet know how to protect its most vulnerable citizens.

Akbari remains in custody in Sari, her fate still uncertain. While rumors of a death sentence circulate, the court has yet to announce its ruling, and each hearing continues to draw the attention of grieving families and a wider public. What keeps the case alive in the national conversation is not only the allegations themselves but the unsettling questions they raise: how a practice rooted in faith could become a tool for exploitation, how a society can better protect its elderly and isolated, and how someone who lived so quietly among her neighbors for years could conceal such a disturbing pattern.

Photograph: بچه مهندس, Wikimedia Commons