While Iran’s regime stubbornly points to drought as the culprit behind the water crisis, the truth is far more complex and disturbing. The horrific water crisis that has befallen Iran is not merely an act of nature. It is the product of a sophisticated corruption machine that has transformed the country’s most vital resource into a goldmine for a narrow circle of generals, politicians, and corporations. At the center of this network stands the regime’s most powerful economic arm—the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its massive construction division, Khatam al-Anbiya. Both exploit their unlimited and uncontrolled power, turning Iran’s lifelines into commodities for the privileged few. This exploitation has left millions of the country’s citizens high and dry, literally.

The Water Mafia: Iran’s Corruption Network That Controls the Flow

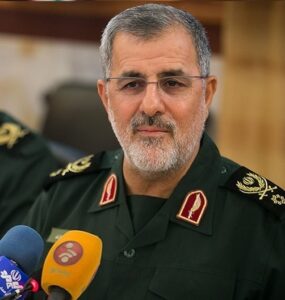

At the apex of the water pyramid now stands General Abdolreza Abed, commander of the Khatam al-Anbiya construction headquarters, who effectively controls Iran’s water infrastructure flow. Under Abed’s command, the headquarters appropriates most of the country’s major water transfer and dam construction projects—often without public tender and lacking any external oversight or transparency requirements. This approach enables the rapid advancement of massive projects while bypassing environmental assessments and supervisory procedures. Ironically, a headquarters intended for construction has become a machine of environmental destruction.

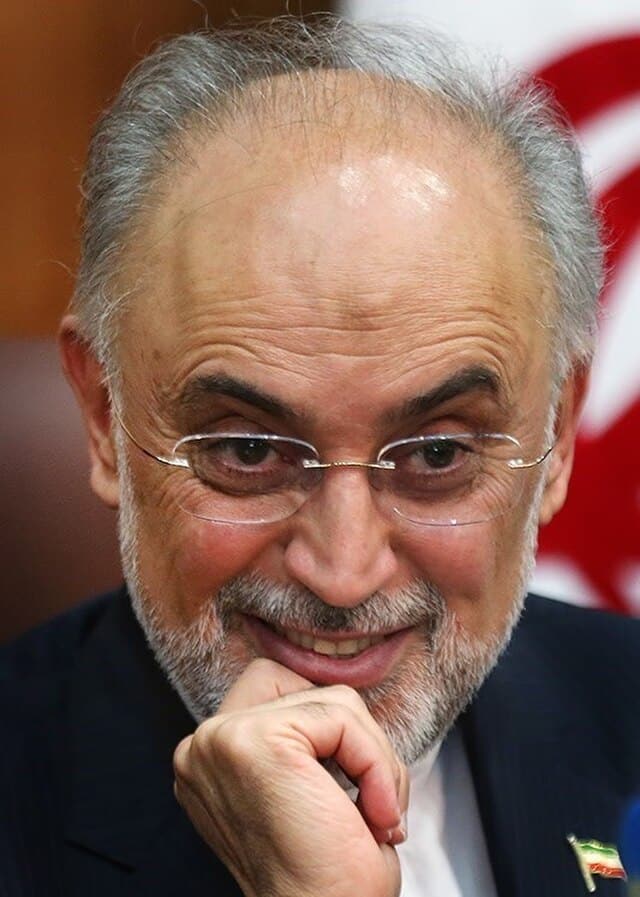

The planning arm of the mafia is the “Mahab Qods company“—a consulting and planning firm considered the “policy setter” of the mafia. Founded in the 1970s, the company controls nearly all water planning in the country, raking in enormous fees and distributing work to affiliated subsidiaries. Eissa Kalantari, former agriculture minister and sharp critic of the system, described Mahab Qods as the “hidden hand” behind Iran’s extensive dam construction and diversion operations. Joining Mahab Qods in the political lobby for the construction of water infrastructure is “Sepasad”—an engineering and contracting company born in the early 1990s as the IRGC’s dam construction arm. Since its establishment, the company has executed dozens of dam construction and water transfer infrastructure projects while completely ignoring social and environmental considerations.

At the center of the machine also stands the Iran Water and Power Development Company (IWPC), the state’s primary contractor responsible for overseeing large-scale infrastructure projects, including dam construction and inter-basin water transfers. The company operates in a joint political lobby with Mahab Qods and Sepasad, creating a power triangle that coordinates among itself the distribution of billions of dollars flowing into water projects.

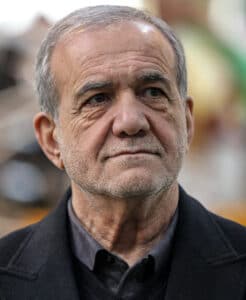

The Gotvand Dam serves as a perfect example of coordinated corruption: IWPC transferred the project to Mahab Qods and Sepasad, and when geologists warned of a massive salt formation at the construction site, officials decided to proceed anyway without informing the public about the risk of increased salinity in the Karun River. Saeed Mohammad, former head of Khatam al-Anbiya headquarters (2019-2022) and of Sepasad, is described as “the architect of the largest and most controversial projects.” Under his command, the Gotvand Dam’s price tag swelled to $3.3 billion— triple the original budget. When the structure predictably failed and required hundreds of millions of dollars in repairs, not only was Mohammad not held accountable, he was promoted to even more senior positions.

Another example illustrating the depth of corruption and its impact on Iranian citizens is the failure of the “Water Supply Jihad”, project executed by the IRGC’s Imam Hassan Mojtaba headquarters. In February 2025, an investigation by the IranWire reported that the project’s goal was to bring water to about 1,500 villages. The execution, however, was limited to laying pipes, and the villages ended up with pipelines but no water. This is the pattern of an established system where the contract and profits matter most, not the practical outcome.

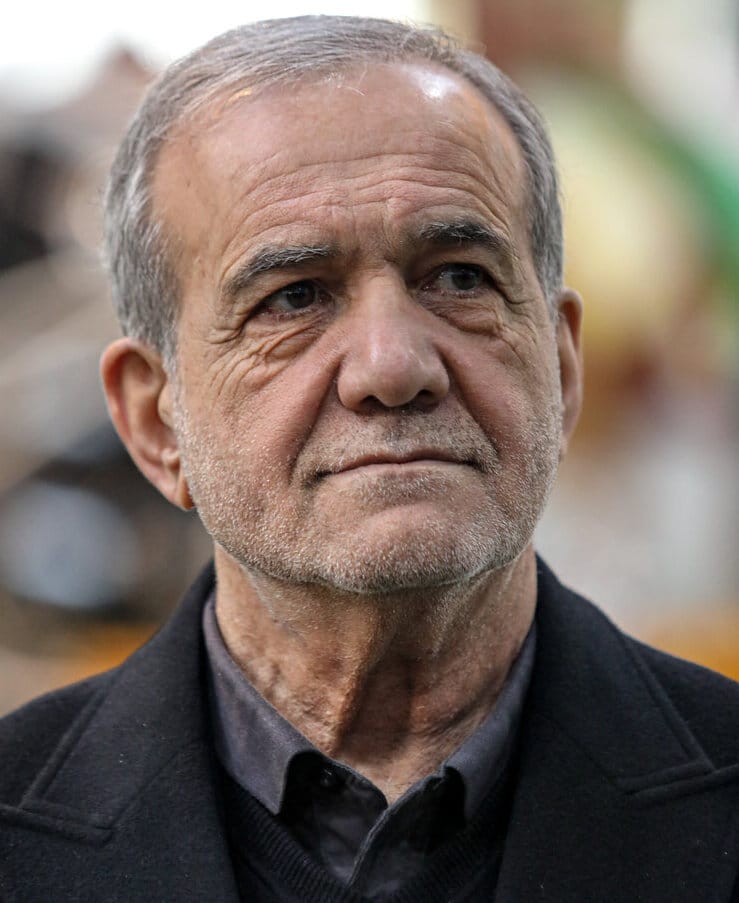

A central figure in the network is Mohammad Javanbakht, CEO of IWPC and former commander in the Khatam al-Anbiya headquarters. His transition from military command positions to civilian water resource management demonstrates the systematic penetration of the Revolutionary Guards into civilian sectors. The system’s structural problem is also revealed in Javanbakht’s strategic appointments, such as his selection of Mahdi Daneshgar, a figure closely connected to Saeed Jalili and the Islamic Revolution Stability Front, to serve as deputy water advisor and general manager of the CEO’s office and parliamentary relations. Iran Wire’s investigation reveals that “whatever Daneshgar dictates to Javanbakht gets implemented.” Daneshgar’s appointment to a key position in water resource management, despite lacking relevant technical background, exposes how political considerations override professional expertise, with Iranian citizens paying the price.

“When the Wells Run Dry: The Human Cost of Elite Greed”

Since the 1990s, the network of interests under the IRGC has pushed for the construction of nearly 750 dams across Iran, many erected hastily and without proper environmental impact assessment. The catastrophic results were not long in coming: river basins dried up completely, groundwater reserves emptied at a staggering pace, and lakes that were natural symbols like the legendary Lake Urmia were almost entirely destroyed. In the Tehran plain, groundwater levels dropped by more than 12 meters within two decades, a decline that caused devastating land subsidence and serious damage to infrastructure.

However, the consequences do not stop at the environmental aspect—Iran’s corrupt water management also carries severe social costs. Entire rural communities were forced to abandon their lands due to water shortages, and their migration to large cities has created social burden and frustration. Meanwhile, mass demonstrations by farmers and residents—in Isfahan, Khuzestan, and other regions—were met with violent suppression, including gunfire, causing serious injuries. The sense of ethnic and regional discrimination, as water is redirected to affiliated industrial areas at the expense of minorities, further intensifies feelings of deprivation and escalated tensions between citizens and the regime.

“Above the Law: How Khamenei’s Protection Racket Shields Water Corruption”

The system operates under the direct protection of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who built dependence on the IRGC to preserve his rule. Under these conditions, the mafia network operates above the law and in the shadows—protected by military influence and legal manipulations that guarantee almost complete immunity. Every time a brave civilian court dares to rule against an illegal dam or destructive project, the ruling is simply cast away—nullified under pressure from “higher” authorities loyal to the regime. Those who try to expose the truth, to break the conspiracy of silence—whistleblowers, journalists, and environmental activists—soon find themselves under attack. In the best case, they face harassment and threats; in the worst case, they’re arrested on espionage charges or sent into exile. As analyst Nik Kowsar testified: “In 2001, I wrote a couple of op-eds criticizing the construction of dams that had a negative environmental impact. President Mohammad Khatami subsequently summoned me to speak with him… Several weeks later, however, I was banned from writing anything about the dams.”

To justify the mafia’s existence, every destructive project is sold to the public as an achievement—another giant canal “to save the center,” another massive desalination plant “in the war against thirst”—while in practice, it’s about more lost billions flowing into the pockets of IRGC commanders and their partners. In other words, the water mafia has an interest in the crisis only getting worse, to justify more projects, budgets, and greater authority for themselves.

The Iranian regime has created a destructive paradox: the military-industrial complex that promises short-term political survival is precisely the one undermining long-term national survival. If Tehran’s taps do indeed run dry, as various government sources and analysts estimate, the Islamic Republic will discover that the Revolutionary Guards’ dams won’t stop the flood of popular rage over decades of systematic theft. Water, the most basic resource for existence, has become a plaything in the hands of generals and tycoons. Thus, while citizens are required to save every drop, the big taps open only for the political elite and their privileged associates.